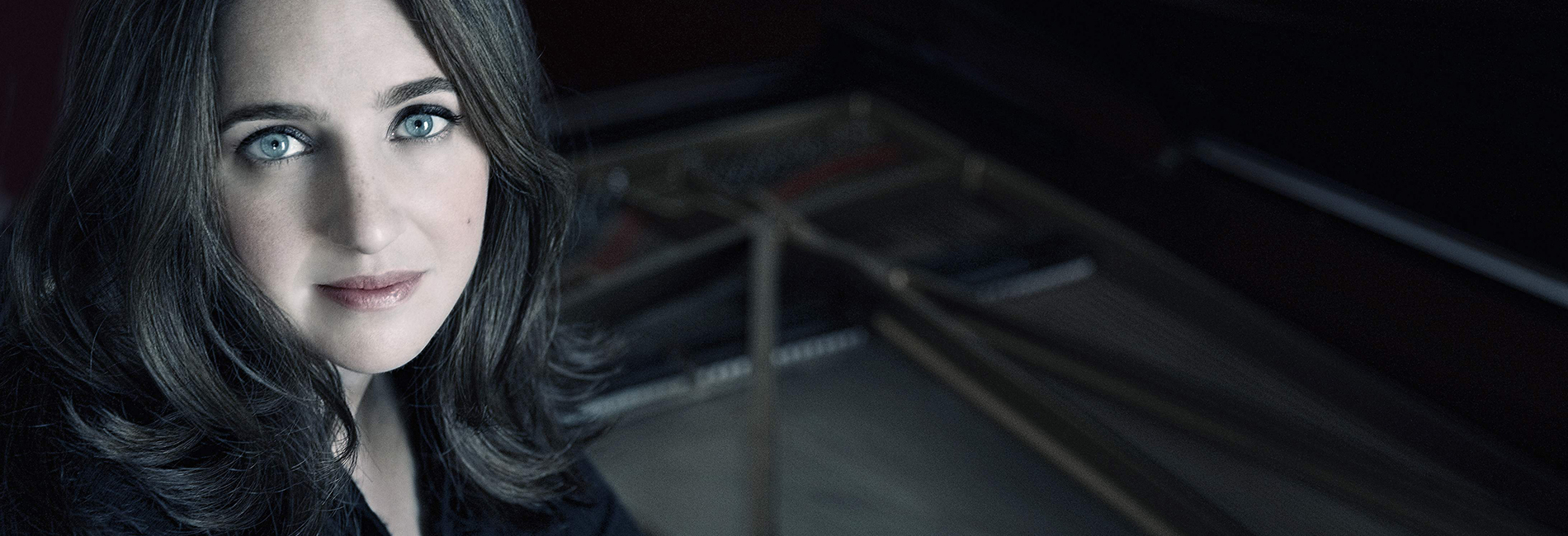

Special Interview with Simone Dinnerstein

Performing at Music Mountain's Winter Concert on February 15 (Sold Out), and returning with Baroklyn on June 14, 2026, to perform at Music Mountain's 97th Summer Festival, which opens on June 7.

The Washington Post has called Simone Dinnerstein “an artist of strikingly original ideas and irrefutable integrity.” She first came to wider public attention in 2007 through her recording of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, reflecting an aesthetic that was both deeply rooted in the score and profoundly idiosyncratic. She is, wrote The New York Times, “a unique voice in the forest of Bach interpretation.”

Music Mountain board president, Barbara von Bechtolsheim, an author, translator and Yale scholar, had a conversation with Simone Dinnerstein on January 27, 2026, for Music Mountain.

Interview

Barbara von Bechtolsheim: Simone, we look forward to your concert on February 15th. Bach Inventions, Philip Glass Etudes, Schubert piano Sonata: how do you design or compose a concert program?

Simone Dinnerstein: This program plays with the differences between Bach and Schubert, using Philip Glass as a bridge between the two.

Glass is so contemporary. He has created a really distinct aesthetic that to me speaks of the past half century. It’s a really iconic sound world. But when I sit down to play Glass I’m struck immediately by all of the non-iconic elements, the contrapuntal and lyrical qualities of his music, the way that it hearkens back to a world before automation just as much as it evokes a modern soundscape. It’s a wonderful context in which to hear Bach’s inventions.

When we listen to Bach, in this case the inventions, we listen with ears which have heard all the music since Bach - and many sounds Bach could not have imagined too. I really want the program to provide a context that forces us (myself included) to listen without knowing where the music fits exactly. These juxtapositions are an attempt to do that, by providing the odd angle that brings a shock of surprised recognition.

This applies equally to the Schubert, like and unlike Glass, so contrapuntal, polyphonic and songful.

Barbara: You might have played Bach Inventions years or even decades ago. How has your understanding and playing of these contrapuntal pieces changed over time? In what way are they still interesting to you?

Simone: The Inventions were among the first pieces I played. The very first pieces I played were the Preludes, then I studied the Inventions. I also had the experience of teaching the two-part Inventions to local children and amateur adults; so I have been on that side as well. It’s just so difficult to have these two parts, which is one reason Bach wrote this music. It’s hard to have your two hands play different roles and to have all of the lines really live together and apart from each other. Of course, as you play more Bach on the keyboard you start adding more and more voices which poses its own problems. But the purity of having just two voices! It’s wonderful.

Barbara: I remember your performance at Music Mountain in the summer of 2024. At the time I was wondering how you connect with the music over and over again. How do you keep this relationship vibrant and fresh?

Simone: It’s a good question. I have asked a few actors that same question because I find it fascinating how they can do that in an extreme way, playing the same role evening after evening. For me it’s less extreme, since I don’t perform as often as actors in a play. Basically, I feel that there is never an end to understanding the music because the music is greater than I can grasp. I don’t ever feel equal to it, and I am always trying to find new ways of approaching the music in order to realize the music ever more clearly. I am always working on my own playing. When I perform, the circumstances are always different: there is a different piano, different acoustics. I feel different based on the day or where in the world I am and how things are at that moment in my life. All these things change my relationship to the music even though I am playing the same music.

There is never an end to understanding the music because the music is greater than I can grasp.

—Simone Dinnerstein

Barbara: We are excited about your Music Mountain program on June 14th when you will perform with your ensemble Baroklyn. How is conducting from the piano different from playing solo or playing with an orchestra while a conductor is in charge? How did this evolve?

Simone: Baroklyn is an ensemble I created in 2017 so that I would have the opportunity to lead a group of musicians playing Bach in the way I had been envisioning, for the strings in particular.

There is a basic divide between two kinds of Bach string playing. One is very influenced by historically-informed performance practice, the current ideas of what performance practice might have been, which is a constantly changing area of research. This approach might suggest certain ideas about vibrato or lack of vibrato, bow length, tempo, rhythm, ornamentation.

There are other string players who have been brought up in a rather conservative, romantic playing style, full of vibrato and with a heavier sound. The listener’s attention is drawn to how well they are playing their instruments.

I did not want to engage with either of those camps. I did not want to think about style as an interpretive master switch or an attempt to create an 18th century subjectivity as a guide. Instead, I think about structures in the music, ideas about expression, ideas about rhetoric, how to make it speak so that we feel the multiplicity of voices. When a group of strings and a keyboard are playing together, they are representative of a group of humans interacting with each other. I think that’s the most fascinating aspect of Bach’s music. There is so much irregularity. Yes, there is a pattern, but he is breaking the pattern. All of this is how individuals are in a society. How do we maintain our individuality within a group? I wanted to have a group of musicians where we could explore that.

Over the years I have become more confident in leading the musicians in this. But it’s a challenge. I don’t like the idea of being in charge and the others following. On the other hand, I want my musical vision to come to life. In our rehearsal process, there is a lot of discussion and a lot of experimentation. It’s very creative and very exciting!

Barbara: Do you play on period instruments?

Simone: I love new sonorities. They can be very inspiring. But I don’t want to be restricted by it having to be of a period. As I said above, 18th century instruments need 18th century ears, and those are hard to find. Imagine never having heard a human-made sound louder than a church bell.

Simone Dinnerstein leads Baroklyn. Photo by Grayson Dantzic

Barbara: From your recordings and from your early excitement about the Goldberg Variations I take it that Bach is your hero. What is it in Bach that fascinates you to this day?

Simone: It’s the multiplicity of voices. As to the Goldberg Variations, there are so many interesting aspects to it. There is a footprint in the piece which is the underlying harmonic structure. This is the ground bass of the aria which is the basis of every single variation. There is this kind of mold within the structure, and every variation has to inhabit that mold, and yet become a completely different animal than the variations around it. It is amazing how Bach is able to do that, to have dances and chorales and arias and sarabandes – all with different affects. Every single one of them is the key of G and inhabits this mold, and yet they sound incredibly varied. Plus, there is an interesting architecture to the work. Every single piece is part of an enormous circle that begins and ends with the aria. It has a feeling of birth and death and rebirth.

Barbara: Bach is not your only hero. You also seem to love Schubert. What other musical influences have shaped your voice, your personal style?

Simone: Yes, Schubert is high up there, I love listening to Schubert Lieder. And I feel very close to the music of Schumann. Over the last ten years or so I have been very affected by the music of Philip Glass. I find his music so incredibly expressive and fascinating and varied. I have enjoyed exploring my relationship with his music and also having the experience of getting to know him. It was very special that he composed a piano concerto for me. That’s when we started to spend time together. I have performed it more than fifty times all over the world – in Europe, all over the US, even in Cuba.

Barbara: You live in Brooklyn, you have a family, you are on tour, you arrange music for your ensemble: this seems almost superhuman. How do you make all of this work?

Simone: I really enjoy living in Brooklyn, it’s where I was born. I live here with my husband and my dog. Family is extremely important to me. I feel very grateful for having the grounding that a close family means. It keeps everything very real. I also find living in NYC a very inspiring place to be. There is so much to see – the museums, the theater, the variety of people. It’s a great, energetic place. I am grateful for living in Brooklyn. For me, living in Manhattan would be overwhelming. It’s important for me to find inspiration around me. Seeing other works of art, outside of music, interesting films or theater, visual art and nature, all of this is inspiration to bring to my artistic life.

Simone Dinnerstein conducting Baroklyn from the piano. Photo by Grayson Dantzic

Barbara: You were passionate about music and about the piano from a very young age on. How do you explain this passion? Were your parents supportive? Did you ever have a childhood?

Simone: I wanted to play the piano, that came from me. My parents were very supportive. My father is a painter, an artist. My mother is a retired early childhood educator. We lived in a household that was centered around my dad’s work, so art was the most important thing. In my parents’ view the highest aspiration you could have was to be some kind of an artist. They did not have a background in music, but they wanted me to do this.

I have always been very self-disciplined, although I could probably have practiced a lot more when I was young. My parents never practiced with me, which is a bit unusual. I started taking lessons when I was seven. When I was nine, I started studying at the Manhattan School of Music Preparatory Division. My wonderful teacher, Solomon Mikowsky, mainly taught college students; he didn’t really make accommodations for me being a kid. From the moment I started playing I knew that’s what I wanted to do. I knew this when I was seven. It’s crazy when you are in your fifties and think back to having made this choice when you were seven. I didn’t know what I was getting myself into. I was influenced by watching old movies of classical pianists and I had a fantasy of what it would be like to be a pianist, a traveling musician. Now I know to be careful what you wish for.

Barbara: Did you have a role model, a hero?

Simone: I had different heroes. Glenn Gould was my biggest hero. Nobody was like him. When I was in my early twenties, I idolized Mitsuko Uchida. There were very few female pianists to look up to. I was besotted with her. I did get to play for her, and she had some really interesting interactions with me where she advised me about various things, which was very generous of her. When I was a teenager, she performed all the Mozart piano sonatas at Lincoln Center. I went to all the concerts, and it was incredibly inspiring.

Barbara: You enjoy playing contemporary music and pieces that you commission. How is rehearsing and playing new pieces different from playing any classical repertoire?

Simone: Philip Glass is quite giving with his music. Part of it is that he himself has performed his own music. He created the Philip Glass ensemble in which he played. I think he understands the sense of ownership a performer has to have while playing. He really allowed me to create the interpretation of his third piano concerto, which has evolved. I am sure it will change again. I changed dynamics or tempi. Occasionally I would ask him whether I could do something like double a note. He was incredibly flexible about that. Also, he has been flexible with me about music that a lot of people have played. I remember when I played Mad Rush in Carnegie Hall. I played it really differently from how he plays it. Afterwards we had a phone call about it. He said you don’t play it anything like I play it, but I really like it.

That’s how I would hope for composers to be. Once they write it, they put it out there; they don’t really own it. Especially if it’s a really good piece of music. I think it’s a mark of a not so interesting piece of music if you feel that there is a limit, there is only one kind of groove. I want to see something in that piece that is true to me about that music. It does not really matter to me if that coincides with the intentions of the composer. I spend a lot of time digging into the music and trying to make sense of it. If you make decisions in one area they affect everything else. So there has to be a cohesion in the interpretation with the music. But the most beautiful music, for me, is the music that is full of possibilities, many of them contradictory.

Barbara: Before we come to an end, I am curious what is special about Music Mountain for you?

Simone: It’s a beautiful place and audience members are devoted to it. I have performed there for many years. It has a very special acoustic and feeling. I find that whole area of Connecticut is special for music. A lot of people there really appreciate music in a very deep way, as something that’s a true need. I think that the connection between music and nature is really profound. Music Mountain is a very special place and because of that musicians have performed there for many years and want to be part of that community.

Simone Dinnerstein in concert. Photo by Blake Nelson.

About the author, Barbara von Bechtolsheim

Barbara von Bechtolsheim, Ph.D, is President of Music Mountain's board of directors. She is an Associate Research Scholar at Yale University. Over the years, Barbara has contributed to the transatlantic dialogue as a translator of contemporary North American literature and as an author. Her recent research about creative couples explores the divide between biographical study and formalistic analysis. In Paare (2022) and Hannah Arendt und Heinrich Blücher (2023) she discusses creative relationships in the context of their respective cultural, historic, and psychological life trajectories.

Barbara von Bechtolsheim, wearing a colorful shawl at Music Mountain in 2023, with her Yale student, Theresa Kauder, who was a volunteer at the concert.